Words -

Critical Essays

Short essays dedicated to cloth, fashion, culture and textiles.

Pant and suit

The garment ensemble and making meaning

M.Phan

March 2020

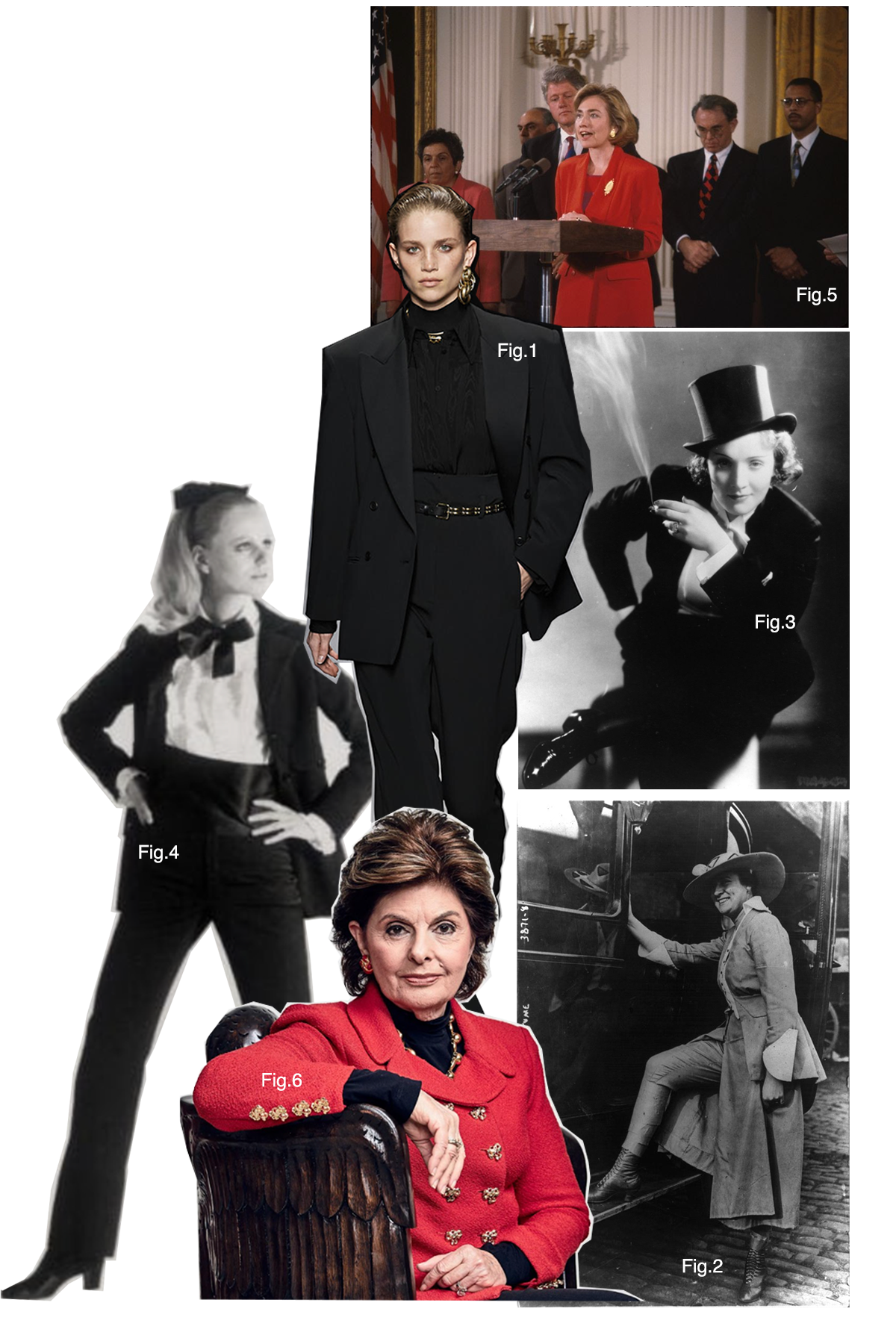

You are what you wear. As Miuccia Prada once said, ‘What you wear is how you present yourself to the world, especially today, when human contacts are so quick. Fashion is instant language’ (Harper’s Bazzar 2018). The medium in scope is the pantsuit, (See Figure 1) or some may interchangeably use the label power suit. This ensemble consists of a tailored trouser and matching jacket, the concept has a long standing history that intertwines social and political justice for females. For women it may symbolise status, masculinity and credibility.

The garment choice has an affirming underlying message it is not solely for the sake of aesthetic purpose. This essay will unravel the insight to the trouser and matching jacket combination. It is more than just an ensemble, there is aesthetic worth behind the pantsuit and it is understood through western cultural capital and context. . .

Read more here︎

Clothing Africa and the Effects of Capitalism

Homogenisation, Westernisation and Stuff.

M.Phan

July 2020

It is not often we consider the post-consumerism effects of our second hand clothes. Author of Clothing Poverty, Brooks claimed that there is a lack of writing in regards to Africa being overlooked within the clothing sector (Brooks 2015). Clothing Africa, through the evolution of capitalism, has contributed to homogenisation and the interconnected complex issues within the fashion system prominent to this day. An examination is in need to detect the influences and how this notion came to be; this would assist us further to understand the current state and the impact it has on the African society. Founder of Humiform, Megan O’Malley stated “People in other countries are often exploited to facilitate western lifestyles.” (O’Malley 2020). Within this writing we will delve into this theme and discuss the issues surrounding fashion in relation to Africa.

This essay will put into scope the different regions and countries of Africa. We discuss the existence of fashion and cultural development. Furthermore this essay will explore the indications to how the west has impacted the local industry and their culture.

Read more here︎

On the note of slow fashion

M.Phan

March 2021

In this contemporary fashion world the category of slow fashion brands seem to have more of a presence to date, this term is often in association with sustainable fashion and identified with the reflection on the speed of production and design practice.

This case study will discuss the definition of slow fashion; its origin, components and elements to this type of practice, and highlight the differences between the collective approaches that exist in the contemporary slow fashion space. In precise, we look at the brand Kowtow (NZ) for contemporary slow fashion and Julie Goodwin Couture (AUS) to analyse the approaches to bespoke fashion making.

Defined in Tailoring a Strategic Approach towards Sustainability (Cataldi, Dickson and Grover, 2010), Slow fashion is described as an approach in which; encourages slow process making to ensure responsible production, adding value to the garment by presenting quality designs, and overall representing a conscious practice where people are to contemplate on the connections of the garment to environment and the maker. Furthermore, the representation of this fashion approach reflects a concise-strategic model often sub categorised in the industry as: eco, sustainable, and ethical fashion (Cataldi, Dickson and Grover, 2010).

The contemporary slow fashion movement can be tied back to a bigger social movement which ignited in the late 1980’s; in Rome Italy where a group of activists responded to the homogenised trend of ‘fast’ consumption business model introduced in the food sector (Fletcher, 2010). Slow Food was started by Carlo Petrini and the initial aim was to defend regional traditions, good food, gastronomic pleasure and a slow pace of life (Slow Food, 2015).

Read more here︎

Design Flaw

Cashing in before the Planet, Waste within the Fashion System

M.Phan

July 2020

The industrial revolution allowed the world’s population to triple, an opportunity for health and quality of life to enhance, and democracy to flourish (Stahel 2019). In addition, Walter Stahel, Founder of Product-Life Institute (Stahel 2019) believes that, ‘Chemistry, engineering and finance opened the floodgates of mass production and turned industrialised countries into societies of abundance’. Within the context of fashion and capitalism; this had brought growth to the global economy, a dossier on Apparel Retail Worldwide reported the global apparel market is projected to grow in value of 1.5 trillion USD in 2020 (O’Connell 2020).

Financial prosperity has been the way to defining success, let alone as a society we have been avoiding to put into scope the relationship between the industrial sector and the ecosystem. Economic growth excludes conversations on the fundamentals; such as deprivation, degradation and inequality (Raworth 2012). In the Journal of Utopian Studies, they present a case on the Anthropocene and the onset of the industrial revolution as the global environment has undergone major alterations as a result of human activity (Brooks et al. 2018). The argument forwarded by leading scientists, as they believe humans have become an influential geologic force significant in the history of Earth (Brooks et al. 2018). Business Insider Australia reported that fashion consumerism and its growing market is taking a toll on the environment (McFall-Johnsen 2019). Alarming findings were disclosed on the waste produced by the fashion system; fashion production makes up 10 percent of humanity’s carbon emissions, contributes to water scarcity and toxic pollution (McFall-Johnsen 2019). In regards to the aspect of consumption, UNECE reported (UNECE 2018); on a global scale, 85 percent of textile is disposed of in landfill each year. This textile waste is enough to fill the Sydney harbour annually (McFall-Johnsen 2019). Post consumption sees the trending matter on released microplastics from laundering of clothes, polluting the marine ecosystem (McFall-Johnsen 2019). It is evident that the current fashion operations create waste through the following three streams; of production, distribution and consumption which is integrated within the traditional linear model. To envisage the story of waste within the fashion system this essay will examine the production process of a clothing article identified below. To further understand the impacts of how a garment creates waste by going on a brief journey through the fashion supply chain.

Read more here ︎

Today’s textile waste as valuable commodity

M.Phan

March 2021

Pre-consumer textile waste in fashion has only been considered and put into conversations within the recent years (Business Wire, 2020). Pre-consumer textile waste is produced through multiple industries and across various stages in the making of a product. This is considering all textile waste created before it lands in the hands of the consumer. Examples of this can include: fabric and yarn sampling, fabric swatches, off-cuts, and excess materials of dead stock and end rolls. Waste management and research provider, Reverse Resources disclosed that there are 37 million tonnes of fiber used by fashion and 25% of that becoming recyclable waste, the total volume is claimed to be at least around 9 million tonnes of industrial recyclable textile waste per annum (Runnel, 2020). The consumption rate in textiles sees no slowing down, in 2016 the global textile consumption marked a historic 100 million tonnes (Messe Frankfurt, 2018); where in the recent Fiber Year 2020 report recorded the total volume to be 120 million tonnes at the present (Engelhardt, 2020).

The market value of recycled textiles ranges from close to the same price of raw material (Runnel, 2020), textile waste has proved itself as a valuable commodity. Innovations in new technologies for re‐using, re‐purposing and recovering value from waste streams are an important avenue for the industries to shift towards the Circular Economy (Boxall et al., 2019). The morbid news of the limitations on earth’s capacity to provide us with an abundance of resources has got the industry thinking about recycling and innovative technology to obtain materials and resources sustainability. Textile waste streams are often unrealised sources of valuable raw materials that can be repurposed or regenerated into profitable new products (Chavan, 2014). Recreated into goods by intelligent collection, sorting, re-engineering and reprocessing (Chavan, 2014).

This essay will highlight the issues in waste in the textile and fashion system as we investigate the factors of how textile waste is created; discussing the activities in waste management and an example of innovation and business capitalizing on this opportunity.

Read more here︎

Compliance and accreditation

Working conditions for ethical business management in the Australian fashion industry

M.Phan

July 2021

Today as we become more socially aware there is a shift in values and attitudes towards purchasing behaviours and decision making. The IBM 2020 report on consumer driving change disclosed that there is an increase in consumers searching for items with ethical and sustainable attributes which aligns with their values (Haller, Lee and Cheung, 2020). Of the 18,980 consumers surveyed, 73 percent indicated transparency is an important factor (Haller, Lee and Cheung, 2020). Many consumers are seeking information on assurances that brands are taking accountability on environmental and social responsibility (Haller, Lee and Cheung, 2020). Furthermore the rise in conscious consumerism in Australia is on the rise, as nine in 10 Australian consumers are more likely to purchase ethical and sustainable products (Arreza, 2020). The above findings indicate that businesses should adhere to the compliance and accreditations in ethical and sustainable business management as this theme becomes a crucial selling point determining the longevity of business survival.

In this essay we focus on the compliance and accreditation for working conditions in relation to the Australian fashion context. It will highlight the regulations affecting working conditions in the apparel industry, and to analyse an accrediting Australian institution supporting this topic of liability.

Read more here︎

The living wage

Ethics in fashion, industry’s issues: inequality and poverty pay.

M.Phan

The year 2021 marks 8 years from the disastrous collapse of the Rana Plaza in Bangladesh. An incident where 1,132 lives were lost to fashion (Hymann, 2019). The aftermath included the emergence of social justice groups and unions to raise awareness of the inequality and exploitation of garment workers; in which these issues still exist today within the fashion industry. Highlighting the ethics in fashion, this can be reflected upon the different areas of the fashion supply chain and industry (Gaskin, 2021). The themes of ethics in fashion are classified in the following areas; labour, sustainability, animal welfare, cultural issues and waste. Ethical fashion aims to reduce the negative impact on people, animals, and the planet (Ethical Made Easy, 2020). The clothes we wear on our bodies would not exist without the people who make them. The underlying question is whether these clothes caused human suffering along the way.

In Bangladesh, a sewing machinist is reported to work over 100 hours a week to make ends meet (Jasmin Malik Chua, 2018).

What is the true cost of the clothes we wear on our bodies?

As reports and data on supply chain transparency become available the topic of paying a living wage has become prominent in the ethical fashion realm. In a commercial setting, making available products at a cheaper price will end up paying the garment workers next to nothing, as Oxfam Australia’s; What She Makes Report (Oxfam Australia, 2019) disclosed that not a single garment worker in Bangladesh was earning a living wage. Some were paid as little as 55 cents per hour (Oxfam Australia, 2019). While clothing is being made overseas in poverty, the fashion companies seem to be the winners claiming the profit ( Baskin, 2019; Clean Clothes Campaign, 2021).

Read more here ︎